© Anton Gvozdikov / shutterstock 633432980

ÖKOBÜRO sees the implementation of an SEA as a unique opportunity to ensure that a balance of interests can be achieved between all stakeholders in large-scale infrastructure projects sooner rather than later. European environmental law, specifically the EU SEA Directive (2001/42/EC), makes the implementation of an SEA mandatory. This means that the possible environmental impacts of official plans and programmes, such as water or waste management plans, land use plans or development plans, simply have to be assessed.

However there is no single standardised SEA law in force in Austria –there are instead a range of different regulations governing air, water, waste management, traffic and spatial development. And these provisions do not contain specifications concerning the extent to which the public must play a role. The result is often that, in practice, the basis for actually improving acceptance through SEAs is lacking. That is why ÖKOBÜRO advocates at legal policy level for the full implementation of the SEA Directive.

More and better SEA procedures

Unlike environmental impact assessments (EIAs), which always refer to a specific project, SEAs are initiated one step earlier in the process when strategic planning considerations are being made. This is the point at which many fundamental questions arise, such as:

- Why is this infrastructure needed?

- Are there any alternatives?

- What impact are the various scenarios expected to have on the environment?

The key to success here lies partly in identifying, assessing and avoiding environmental impacts at an early stage.Taking potential environmental impacts into account at an early stage prevents avoidable environmental damage and reduces the costs associated with changing the plans or with compensatory measures.

The second success factor is the involvement of the concerned public from the very beginning. This approach ensures that, once a thorough SEA has been performed, involved environmental organisations can testify that the submitted plan has been jointly assessed for its environmental impacts and that it represents the best possible option.

This creates a sense of acceptance and understanding and defuses conflicts over individual projects. SEAs should not, therefore, be seen as a way of replacing subsequent EIAs, but as useful additions. If a programme or plan contains multiple projects, the subsequent EIAs can all refer to and build on the findings of this one SEA.

Examples of high acceptance thanks to SEA at the round table

In Vienna, the construction of new waste incineration plants was long met with fierce resistance from residents and citizens’ initiatives. To increase the acceptance of waste incineration, the City of Vienna had an implementation concept for an SEA drawn up, which placed particular emphasis on public participation. This “Viennese model”, also referred to as “SEA at the round table”, brought several environmental protection organisations – including ÖKOBÜRO – and independent experts together in 1999, and tasked them with joining forces to develop a waste management plan for the coming years.

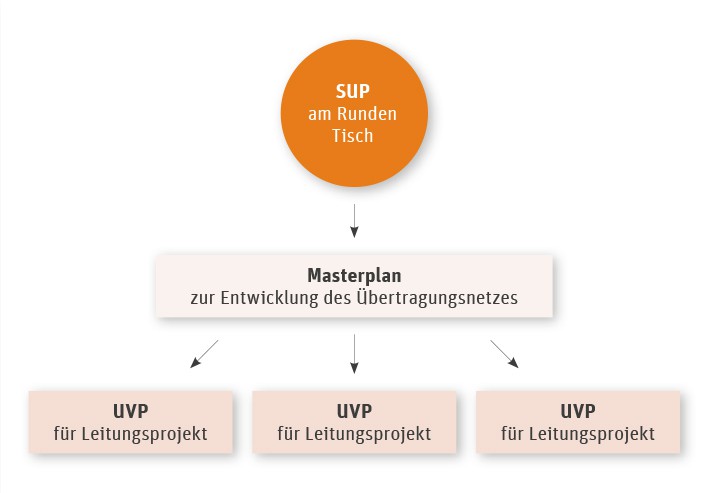

One SEA (SUP in German) may be the basis for several EIA (UVP) proceedings. The graphic shows that a master plan for the power grid is being developed in a SEA. This master plan is the basis for the EIA for several power lines.

The aim of this SEA at the round table was to find the best way to deal with the waste that the city was expected to produce, taking all factors into consideration. When performing the SEA, the participants had all the data from the relevant Viennese Municipal Department (MD 48) to hand, enabling them to jointly examine a variety of scenarios and alternatives. Waste incineration proved to be environmentally superior to other forms of waste disposal, a fact that the environmental protection organisations in the SEA team were ultimately confident of. In addition to the construction of another waste incineration plant, supportive measures for waste prevention and separation were also agreed upon in the course of the SEA.

This first SEA at the round table was followed by the EIA procedure for the Simmering waste incineration plant. Unlike the previous approval procedures for waste incineration plants, this project was able to move forward without any significant opposition. Vienna’s need for the additional plant and its safe operation for the general public were legitimised by the transparent participation of the public in the SEA. What’s more, the participating environmental protection organisations had ensured that the plant would meet the highest environmental and health standards.

Based on this positive experience, MA 48 has since voluntarily renewed its waste management plan and, ever since 2013, has vowed to renew an additional waste prevention plan every five years as part of an SEA at the round table.

The waste incineration plant in Vienna-Simmering. Result of the first round table SEA.

© Fotoclub

The state government of Burgenland also voluntarily subjected the zoning for wind power plants in the north of the region to an SEA at the round table. As a result, wind power in Burgenland is now uncontested and already covers more than the entire electricity consumption of the province in financial terms. In Lower Austria, however, the lack of such a consensus plan led to an uncontrolled expansion of wind power for a long time. Strong opposition from the general public finally caused the Lower Austrian state government to apply the emergency brake in 2013 and even enacted a temporary ban on approvals for wind turbines.

Wind turbines near Weiden in Northern Burgenland. Undisputed thanks to the round table SEA.

© Nina Holler